Although the Confessions podcast is often a fascinating, rewarding listen, I cleave to the axiom that Unherd should remain unread. Thus, I have only just got around to reading the piece penned by the Rev Dr Giles Fraser, entitled:

It is admirably concise (it will take you no more than five minutes to read), but despite (or perhaps because of) its brevity, it is an extremely muddled pitch. This is not to say that I do not agree with anything that he said; indeed some points had me inwardly cheering.

Of course the decline in family and community life is a matter of regret. Clearly we need to question whether it is morally right to contract out the care of our beloved relatives to (often) low-paid migrant workers. Obviously the state of our Health and Social Care provision in the UK is a cause of deep concern. Undeniably the peripatetic nature of modern life poses particular challenges for human flourishing. And moreover, given that Fraser is not only a Christian, but also a clergyman, we should not be surprised by what most would see as a rather traditional point of view. It is the rôle of a preacher, after all, to ‘comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable’. Had Jesus stuck to emollient banality then it is unlikely he would have been crucified.

Like Fraser, I am a Christian, though I am a Catholic and Fraser is an Anglican, so I have to give due consideration to Catholic Social Teaching (CST). This is not to say that CST provides clear, dogmatic guidance on socio-economic question, or that it ‘belongs’ only to Catholics. One of the foremost contemporary proponents of CST is the ‘Blue Labour’ Peer, Maurice Glasman, who is Jewish.

Furthermore, like Fraser, I am broadly pro-Leave. But I have no hunger for a ‘No Deal’ Brexit. Fraser, on the other hand, is not only willing to countenance ‘No Deal’ but actively hoping for it:

“I am longing for a full-on Brexit – No Deal, please – to come along.”

Giles Fraser, ibid.

The biggest difference between us, though, is that I am on the right and, ceteris paribus, in favour of freer markets, whereas Fraser is on the Left and more likely to look to the state.

The foundational myth of the piece concerns a woman who phones her GP to ask if someone might be sent round to clean up her elderly father, who has soiled himself. The GP asks whether the woman would have expected the state to change her babies’ nappies. Fraser suggests that the responsibility for cleaning the old man’s bottom is one that, as a matter of natural justice, falls to his own family.

The real difficulties arise, though, when he lays the blame for this sorry state of affairs at the door of ‘Neoliberalism’ (a.k.a. the ‘Free Market’, a.k.a. ‘Capitalism’, a.k.a. ‘Globalisation’, a.k.a. ‘Free Movement’). Lurking beneath his piece is the implicit point that if we can only crush capitalism, or extricate ourselves from Globalisation, then these social ills will be solved. If not this, then certainly that Globalisation has either created or exacerbated these social problems.

The initial story seems odd, to say the least. It is true that many people expect the state to perform functions which were formerly the responsibility of families. We have all heard about 5 year old children arriving at primary school neither toilet trained nor with adequate command of their mother tongue. These children are not usually the offspring of smug, middle-class remainers who have subcontracted their childrearing to Bulgarian nannies. It is a sign of a far deeper societal malaise and perhaps those on the Left need to interrogate themselves about the extent to which successive governments have created a culture of dependence upon the state. Five year olds are not going to school wearing nappies because their parents are Libertarians who have taken the creed of individual rights and personal choice slightly too far.

I do not doubt the veracity of the anecdote, but I do wonder about the accuracy of its retelling. The picture painted is of a woman who apparently lets her elderly father sit in his own ordure while she phones his GP. By any measure, that is not the normal response of a human being. But let us assume that this entitled, capitalist monster has chosen to pursue “individual acquisition” (i.e. have a career) over filial piety, or has committed the other mortal sin in Fraser’s universe: that of moving away from her own community (and thus her father). It would be quite reasonable for such a woman — such a daughter — to contact her father’s GP to ask how her father might be better looked after, and what Local Authority help might be available.

We have a tax-payer funded state system of healthcare, and a parallel (though patchy) system of social care, or assistance for carers. As the man’s daughter is assumed to be his carer, then the question is whether she is entitled to Local Authority help. Under the Care Act 2014, Councils across England have a statutory role in assessing the support needs of carers, and whether assistance is given will depend upon a number of variables, including their earnings and assets.

What Fraser seems to be implying (though he never quite says so) is that an end to Free Movement of Labour will somehow lead to a return to families, and not the state, caring for elderly relatives. People will not leave their native communities, and their heads will not be turned by “the capitalist dream of individual acquisition and self-advancement.”

There are a number of problems with this implied argument. The first is the fallacy cum hoc ergo propter hoc — just because our current system of health and social care is being, to a large extent, ‘propped up’ by EU workers, it does not follow that these workers, or the EEA Freedom of Movement that allows them to work here, has caused the system. The system was created, over many years, by successive UK governments.

This system, in serving a need, has therefore created a demand and an expectation. It has created ‘dependency’. Simply to withdraw it would not lead to a peaceful return to the social norms of 40 years ago, just as prohibition did not create a nation of teetotallers in 1920s America. The departure of a significant proportion of a workforce is more likely to lead to a crisis in provision. There are not thousands of UK citizens desperate to work in the care sector, and even if they can be recruited quickly, they will need to be trained. As Fraser frames it, EU (actually EEA) Freedom of Movement, works to benefit “the rich” at the expense of the poor. But any breakdown in social care provision will have less of an impact upon the wealthy because they will be better able to afford private provision.

Rather than employing Agnieszka or Bogdan, who are paid at least the minimum wage, enjoy statutory employment protections, pay tax, etc., the wealthy are also better placed to employ carers who may be illegal migrants, and thus unprotected, poorly paid, and untrained. The loser in any social care crisis is far more likely to be the working class single mother who in addition to caring for her elderly father, is also ‘carer’ (i.e. mother) to two children of her own, and juggling everything with the part time job she holds down in order to avoid a life on benefits. If the assistance that the state currently gives her disappears, then she may not be able to find alternative help so easily. So she gives up her job. The family unit is perhaps strengthened in Fraser’s view, but at what cost? Without income, at least one cost is increased — dependence upon welfare.

In the Giles-Fraserverse, where every family is like the happy Pakistani families he witnessed in the restaurant in Tooting, the answer is always going to be a network of families constituting a “buzzy hub of a homogeneous society”. This is an attractive vision but surely, as a pastor, Fraser must realise that the reality of peoples’ lives is very different. The imaginary single mother I mentioned above may not have chosen the life she finds herself living. She might have been abandoned by a feckless partner, or escaped an abusive one. She may be a widow. She may have serious health issues of her own. Perhaps she would love to be a housewife, caring for her children and her elderly father while her husband brings home the bacon. But for whatever reason, this is not the life that she has.

I agree with Fraser, absolutely, that the family is the basic unit of society, and should be encouraged, nurtured and protected. I agree too that family and community are the most effective forms of social care. However, where I take issue is both with his romanticised vision of family life, and his suggestion that a good, hard Brexit will herald a return to former, halcyon days:

Given that I spend half my time on this blog arguing that we should learn from the wisdom of Aristotle (who died 1700 years ago) and Aquinas (who died 745 years ago), and a considerable amount of time on Twitter complaining when people use ‘Medieval’ as a pejorative, it might seem odd that I am suspicious of Fraser’s Golden Age Fallacy. But while I believe that there were many good, humane and wise things to be celebrated about Ancient Athens or Medieval Europe, I would not wish to be without electricity, printing, penicillin, vaccines or trains.

Fraser talks of being “socially conservative” and lauds “traditional values”, but there is a danger here. Traditionalism is not the same thing as conservatism (keeping things the same), still less archeologism (the older the better). The word ‘tradition’ is derived from the Latin word meaning to ‘pass on’ or ‘hand down’ (tradere); so whilst this clearly implies not being forgetful of the past, it does not necessarily entail keeping everything the same, nor does it exclude progress. The tricky part is deciding what is worth conserving, and what needs to be jettisoned or improved. (For a careful analysis of this question, I recommend reading Alasdair MacIntyre’s masterful After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory [Notre Dame, 1981].) The democracy and social cohesion of Aristotle’s Athens rested on a sea of slaves and excluded even free-born women, after all.

While social conservatives rightly regret the rise in divorce and its contribution to family breakdown, there can be little doubt that until comparatively recently many women were condemned to endure relationships that were often inhuman and abusive. The example of family-based social care that Fraser chooses to uphold is also noteworthy — that of ‘conservative’ Muslim families whom he praises for their lack of integration, whereby they have avoided the cancer of “progressive individualism”. Once again, though there is doubtless much that we would admire here in terms of the place given to home and family, what other cultural mores sustain this way of life? How many of the women in that restaurant have careers, or a university education, for example? Are there different expectations for the sons than for the daughters?

Many who regret the breakdown in family life and the growth of social alienation are tempted to want to ‘turn back the clock’, but that is not possible. Also, not all changes in the lives of families and communities are cultural or societal. What really enabled women, especially working class women, to play a fuller part in society and have careers outside the home, where technology and commerce (Fraser’s hated ‘capitalism’ in other words). It was not simply that their husbands, or society as a whole, one day became convinced by arguments for sexual equality, but a host of other factors that meant it was a practical possibility. Affordable domestic appliances meant that cooking and cleaning was no longer a full time job, cheaper cars and the appearance of supermarkets meant that shopping for food no longer required a daily trip to the butcher, the baker, the greengrocer and the fishmonger. Alongside this, growing prosperity has led to greater longevity and medical advances. My grandparents, born between the Wars, all lived into their 90s, whereas their parents had died in their 50s, 60s or 70s. The daughter (or son) expected to care for an elderly parent nowadays might herself be well into her 70s.

Once again, I should say that I am extremely sympathetic to one of Fraser’s points, viz. that the decline of the family as the basic building block of society is to be deprecated. However, what I take issue with is the way in which he seeks to pin the blame for this decline solely and squarely at the door of the free market, in particular, free movement. He is, at least, consistent enough to oppose not just free movement between countries, but between towns and villages in the same country:

“This is the philosophy that preaches freedom of movement, the Remainers’ golden cow. And it is this same philosophy that encourages bright working-class children to leave their communities to become rootless Rōnin, loyal to nothing but the capitalist dream of individual acquisition and self-advancement.”

idem.

Free movement has not only involved poor Eastern Europeans coming to the UK to take low-paid jobs wiping elderly British bottoms. It has enabled British people to travel abroad on holiday and to retire to the Costa Brava. These are not the George Osbornes with chalets in Swiss ski resorts, but working class people whose parents never dreamt of anything more exotic than a static caravan in Great Yarmouth. I’ve heard many ‘Club Class’ travellers sneer at low cost airlines, disguising their snobbery by dressing it up in environmental concern about CO2 emissions and the damage done to ares of outstanding national beauty in the Mediterranean. One cannot help feeling, though, that it actually springs from the belief that it is only ‘people like us’ who ought to travel, not ‘people like them’. We are travellers, the plebs are merely tourists. How different — really — is Fraser with his rose-tinted bucolic vision of an England where people stay where they ‘belong’?

Catholic Social Teaching has, from the time of Pope Paul VI’s 1967 encyclical Populorum Progressio been consistently in favour of migration per se (i.e. welcoming refugees as fellow children of God), yet suspicious of the other aspect of Globalisation, the free market. Pope Paul wrote:

“Trade relations can no longer be based solely on the principle of free, unchecked competition, for it very often creates an economic dictatorship.”

Pope Paul VI, Populorum Progression, 1967

Although this was a widely held view among ‘progressive’ economists at the time, it quickly became apparent that the reality was very different. In fact it was those countries where the state intervened most aggressively to ensure ‘fairness’ and to ‘check competition’ where people were more likely to languish in poverty and live lives of unnecessary hardship. As Professor Philip Booth pointed out in a lecture on CST and Economic Nationalism:

“Professor Sir Paul Collier once noted that the bribe to get into the training school for customs officers in Madagascar was 50 times the per capita annual income – such a job in a country with high trade barriers is a well-trodden path to enrichment (rather like a tax collector in Jesus’ time). The attempts by government to direct development in particular sectors, or protect domestic markets, or promote policies of import substitution have often promoted mass poverty and corruption or, at best, hindered economic growth.”

Philip Booth, in a talk given at the Pontificia Università Lateranense, March 28, 2017

The tone of papal teaching slowly caught up, and by the time of Centesimus Annus (Pope St John Paul II) in 1991, the Pope remarked that it was those countries that had integrated into international markets that had developed most quickly and that prevailing views had changed when it came to free trade. Pope Benedict XVI later reminded us in Caritas in Veritate about the importance of developed countries opening their markets to the exports of poorer countries — not only aid, but trade.

Giles Fraser seems to be in tune with CST with respect to the requirement to be generous to refugees. On 4 January of this year he wrote another piece on Unherd entitled Brexit Britain should welcome more refugees. Back in 2015, when he was still the Loose Canon and not yet the ‘Leave Canon’, he penned a Guardian article with the rather uncompromising title, Christian politicians won’t say it, but the Bible is clear: let the refugees in, every last one. Thus he seems to be quite liberal when it comes to ‘conventional’ refugees, but no fan of economic migrants. This looks dangerously like being in favour of migration, just as long as it is never economically productive.

One of the aspects of Fraser’s piece with which I most keenly take issue is his suggestion that the only ‘winners’ from free markets and movements are ‘wealthy Remainers’. This is a common view on the Left, which seeks to divide any political or economic system into ‘oppressors’ and ‘the exploited’, and for all that we would expect to read it in an essay written by a 16 year old member of Momentum, we should expect more of Dr Fraser. It is easy to forget, now, what a terrible state Eastern European nations were in after the fall of Communism in 1989-90. Membership of the EU in 2004 for eight former Communist states represented a huge opportunity for their citizens. It not only opened up their trade to the whole of the EEA, but allowed their citizens to seek employment abroad. One has to balance this with the dangers faced by an emerging economy should all of its young and energetic citizens leave, but there is no doubt that the wages sent home played a significant part in rebuilding those countries (and still do). Fraser’s rather simplistic view of the EEA Single Market (in which these pioneer migrant workers can only be ‘exploited’) only makes sense if economic exchange is a zero sum game, and even the briefest examination of rising prosperity worldwide shows that it is demonstrably not.

In the midst of Fraser’s rant there stands a huge and unavoidable elephant: namely state intervention in the economy, and government welfare policy. For all that CST tends to be somewhat suspicious of the free market, JPII’s Centesimus Annus (1991) did not hold back on the subject of the tendency of the modern state to create a dehumanising dependency upon welfare:

By intervening directly and depriving society of its responsibility, the Social Assistance State leads to a loss of human energies and an inordinate increase of public agencies, which are dominated more by bureaucratic ways of thinking than by concern for serving their clients, and which are accompanied by an enormous increase in spending. In fact, it would appear that needs are best understood and satisfied by people who are closest to them and who act as neighbours to those in need. . . . One thinks of the condition of refugees, immigrants, the elderly, the sick, and all those in circumstances which call for assistance: all these people can be helped effectively only by those who offer them genuine fraternal support, in addition to the necessary care.

Centesimus Annus, ¶148

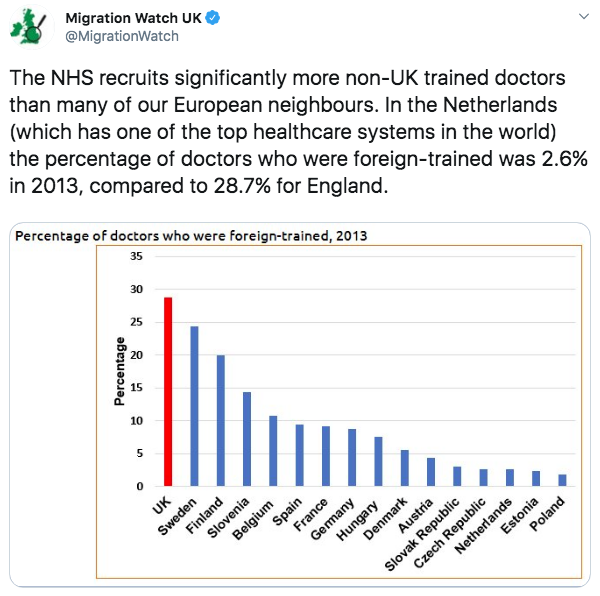

It may well be that Globalisation has made this state of affairs easier for governments to achieve, but it has hardly forced their hand. Fraser takes the lazy leftist way out — blame the free market, not the overweening state. If it were simply the hated free market or exploitative freedom of movement that were to blame for our current malaise then other relatively wealthy Western European countries would be experiencing the same phenomena, but this is not the case. The UK relies upon an unusually high proportion of non-UK trained doctors, for example:

Of the 15 countries on this graph that rely upon fewer foreign trained doctors (per capita) than we do, eight have higher wages in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms. Why has free movement not had a similarly deleterious effect on those countries that Fraser claims it has had on the UK? One of the countries with the lowest proportion of foreign-trained doctors is The Netherlands, and yet its GDP (PPP) per capita is 25% higher than the UK’s.

Therefore, if Fraser were truly convinced that the answer to society’s ills were to be found in the restoration of the family to the centre of British social life and a sweeping away of those policies which frustrate that, then he ought to be more honest about what is standing in the way of this. But as he is, I assume, a Corbyn supporter:

… then only criticism of the discredited dogma of ‘neoliberlaism’ is fair game. Corbyn, by his own admission, intends vastly to increase the power of the state and its rôle in our lives. Just as Fraser argues (after a fashion) that neoliberalism and free movement have weakened society, one might equally argue that more and more state intervention has been to blame. Out of a decent desire to protect the poorest and most vulnerable in society, we have created a system which has disempowered, deskilled and even dehumanised people. And as Fraser half-recognises, it is the wealthy that will be able to game the system. Just as a wealthy family is able to afford to employ a carer, so they are able to ensure, via a complicated web of living gifts, property-related shenanigans and trust-funds, that Grandpapa receives the maximum possible assistance from the state.

I would have far more sympathy for Fraser’s arguments had he widened his field of fire to include state intervention, not just the free market. Insofar as Fraser’s pitch was anti-capitalist and anti-EU, he will have earned the approval of many, if not most, Corbynistas. But his socially conservative focus upon the family will doubtless have appealed to many ‘Blue Labour’ supporters, too. I doubt there is anything I could say to sway the Corbynistas, but to the Blue Labour folk, I would just remind them of how that apostle of Catholic Social Teaching, Lord Glasman sees things:

“The reconciliation of estranged interests, is fundamental to a good society . . . and it is the work of no one institution alone.”

Maurice Glasman, in Blue Labour: Forging a New Politics, ed. Ian Geary & Adrian Pabst

Whatever one thinks about Globalisation, we now live in an interconnected and increasingly complex world. If we are to build or rebuild a society based around the Common Good, then it will not be something achieved by focusing on simplistic binary choices (like ‘Working Class honest-as-the-day-is-long Leave’ versus ‘Middle Class Lickspittle capitalist lackey Remain’). It will require the “reconciliation of estranged interests”. Giles Fraser’s article does nothing to further that, but it has got people talking and that can only be a good thing.