As things turned out, the number of idiots determined to score political points relating to Brexit during the World Cup (so far, and pace Martin Selmayr) proved to be comparatively small. It’s difficult to give voice to a divisive message when the whole nation is united behind a united team and their self-effacing manager. Gary Lineker, left twiddling his thumbs while ITV screened the semi-final, took to Twitter to bemoan clueless politicians whom he felt were jumping on the bandwagon to bolster their own credentials. I am sure that next time a sporting pundit wades into a political debate, he or she will get short shrift from Gary.

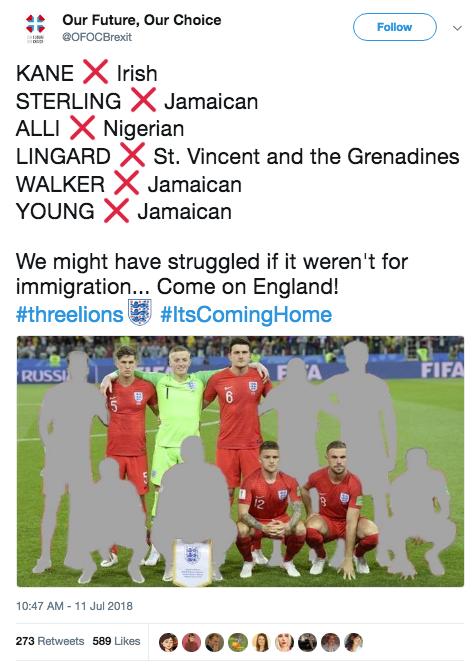

But on the morning of the semis, another tweet — well-meaning but misjudged — caught my eye. It came from Our Future, Our Choice, which describes itself as “a group of young people campaigning for a #PeoplesVote on the Brexit deal!”

If you’ve come to this article because you follow me on Twitter, then you already know that I am generally pretty pro-immigration, within sensible limits. Unsurprisingly, then, my initial reaction to seeing this tweet was positive — OFOC were making a reasonable point about the contribution that players with immigrant background made to our national side. But then I made the mistake of thinking about it. Two things troubled me. I recognise that Twitter is, by its nature, concise and unsuited to conveying subtlety or detail, but listing the names of six players alongside their ‘original’ nationalities might have been read in other ways. Illustrating the tweet with a photo of the England side in which those with ‘foreign origins’ had been greyed-out also seemed to be a rather foolish move.

I was probably overthinking it, but ask yourself this: what if this Tweet had been put out by a racist outfit like the BNP or EDL? How would we have read the greying-out of (mostly) non-white players and the list of some players’ non-English origins then?

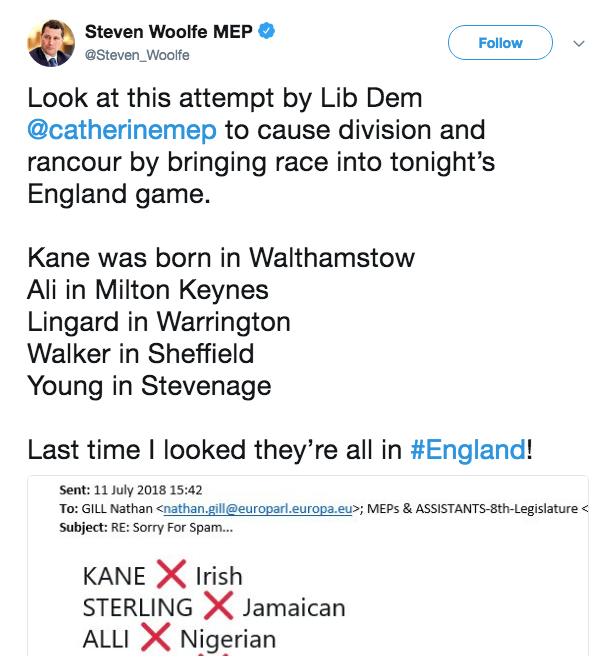

This notwithstanding, I wasn’t especially troubled until I saw a later tweet from the erstwhile UKIP and now independent MEP, Steven Woolfe, who had taken umbrage after the Liberal Democrat MEP and EU fanatic Catherine Bearder had sent a link to the Tweet to her fellow MEPs.

It’s political point-scoring, of course. Bearder was undoubtedly trying to score a point against her benighted UKIP colleagues by reminding them that some of the England players could not have been able to trace back their English ancestry to the Norman Conquest. She might have expected Woolfe, a man with an Irish grandmother and a black (American) father, to feel slighted, and sure enough he took the bait. But Woolfe’s own Tweet exposes his own prejudices. He lists the birthplaces of 5 of the six players listed in the original tweet, but omits the name of Raheem Sterling, who was born in Jamaica.

Was that simply an oversight, or was it because Sterling does not fit Woolfe’s definition of ‘Englishness’ as something conferred by birth within the territory of Britain/England? Was he suggesting that Sterling was less ‘English’ than his team-mates? I have no idea. But if OFOC and then Bearder were unwise to have raised the topic of race/ethnicity, then Woolfe showed a similar lack of savoir-faire in his response.

The FIFA Rules of the Game, which were amended a decade ago after Brazilian players started appearing for Qatar and Togo, are clear (in §7) that in order to play for a particular territory a player must have been:

- born in the territory

- born to a parent born in the territory

- descended from a grandparent born in the territory

- been resident in the territory for at least 5 years after the age of 18

It’s often regarded as an anomaly that the United Kingdom has four national teams, all sharing British citizenship (England, N.I., Wales, Scotland), but that is only the beginning of it. There are 11 ‘national’ teams the players of which have British nationality, including Montserrat, Bermuda and Gibraltar. FIFA rules here mean that, say, a Gibraltarian, Cayman Islander or Scots footballer could, if they so wished, play for England after two years’ residency.

But FIFA rules aside, how do we understand nationality and citizenship? The original tweet picked out Harry Kane (“Irish”) and players who are black or mixed race. The list of players with ‘foreign’ ancestry is, I suspect, rather longer. Harry Maguire and Jordan Pickford both went to Catholic schools, so I’d be surprised if there wasn’t at least an Irish granny in the mix there.

Why none of this matters is that Britain (or the UK, and therefore, derivatively, England) has a civic rather than an ethnic conception of nationhood, and therefore citizenship. Civic nationhood coalesces, first of all, around a democratic nation state. Indeed, the democratic identity of the nation is essential; for only democratic, liberal states tend to welcome new members. I have no idea what point OFOC and Woolfe (or even Bearder) were trying to make, but what counts is someone’s nationality — not where they were born (cf. Woolfe), or where their ancestors were born (cf. Bearder). Black or white, Catholic or Protestant, UK born or foreign born, what we saw was an English team working together, which is an example of solidarity. We will, I am sure, see the same solidarity on Saturday in the play-off for third place.

Solidarity (‘friendship’ or ‘social charity’) is a term often misused and misunderstood, especially in the social media. Solidarity is not virtue-signalling, but a genuine working together for the common good. It is solidarity that can make nationalism — too often a synonym for isolationist racism — a force for good. It is nationalism that binds us together and allows us to accept democratic decisions; it is nationalism that allows us accept the imposition of taxes that might be spent largely upon others; it is nationalism that permits us to welcome, for example, refugees as a nation and not simply as individuals.

Perhaps in the end, Lineker was right. Politicians ought to steer clear of football if they are trying to score political points (although to be fair to Boris Johnson, I am not sure that was his intention). Football, more than any other, is a tribal game. I’ve heard Liverpool fans claim that they really don’t care about the fortunes of the national side because all that matters is club football, I’ve seen Geordies in my local pub both wanting Jordan Pickford to save every ball and yet worrying that he’s a Mackem (from Sunderland).

What the World Cup has shown us is that nationalism — that is, civic nationalism — can be a beautiful thing, but only when it about what binds us together, and not what divides us.